What Does “Dual-use” Stand for?

Laura Del Vecchio

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

In its literal meaning, dual-use is anything containing both "positive" and "negative" implications. More specifically, the term dual-use applies to quandaries related to technology use —or misuse— in civilian and military contexts. For instance, technologies that could amplify peaceful agreements or undermine security objectives.

In the context of trade, the European Commission states that “[...] ‘dual-use items’ shall mean items, including software and technology, which can be used for both civil and military purposes.” The Office of Science Policy of the US National Institutes of Health defines dual-use as, “[...] knowledge, information, products, or technologies that could be directly misapplied to pose a significant threat with broad potential consequences to public health and safety, agricultural crops and other plants, animals, the environment, material, or national security.”

These definitions are denoted to help policymakers evaluate the impact of technologies applied to specific contexts, whereas the criteria that distinguish the legitimate use and misuse of technologies are values of the context. So, what kind of technologies are we referencing here?

Tech Implications

Toy warfare

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Toy warfare

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

By its very nature, technology tends to have more than one use. The technological domain of Artificial Intelligence (AI), for instance, has applications designed to help predict acute crises related to Climate Change, such as the Machine Learning Weather Model, and others that assist in operations where unmanned vehicles perform hostile attacks on communities or entire nations. The former tends to be positively perceived, while the latter can instinctively generate controversies about “why,” “when” or “how” it came to the point of using technological objects with malicious intentions. Any technology can produce both feelings.

From Smart Contracts to Facial Recognition tools, the contradiction of dual-use technologies surpasses the domains of technological developments. It frames the ethical decisions of those who use these technologies, in which the categories of “good” or “bad” could be seen as interpretations.

- applicationSmart ContractapplicationSmart Contract

In the blockchain, smart contracts are self-executing and automatic programs with specific terms that allow peer-to-peer transactions to take place without a third-party guarantee.

- applicationFacial RecognitionapplicationFacial Recognition

A biometric tool that employs machine vision to recognize a human's identity through unique facial traits and expressions.

In an article published by ISSUES, researchers argue that “[...] beyond disarmament treaties, countries use various export-control instruments to regulate the movement of dual-use goods. However, this is constructed around moral and ethical interpretations of what constitutes good (dual-use) and bad (misuse).”

This leads us to the question of whether the ambivalence of dual-use technologies is caused by those inventing these technologies or by their own nature of change that can swerve according to time, needs, and a long list of variables, such as warfare conflicts —which often change depending on political, economic or social needs and interests.

To help shed light on such intricate matters, Laura Del Vecchio, editor-in-chief at Envisioning, and Quentin Ladetto, head of technology foresight at Swiss DoD, had a conversation about technologies for peacekeeping and other topics related to dual-use.

💡

The present article is part of the Dual-use project, which aims at pursuing answers to the many questions regarding the application of emerging technologies related to peacekeeping and also to dual use research. Together with this editorial piece, you will find a Case Study on the impact of multilateralism on data sharing for building peace agreements and enabling migration policies, and a Sci-fi Chronicle that takes a step into utopian discourses of inclusive futures, where societies of tomorrow are part of a solid effort to create global governance of long-term peace.

Laura Del Vecchio: Do you believe that emerging technologies can help strengthen peace agreements?

Quentin Ladetto: Technologies, if understood as coherent bodies of knowledge and practices based on scientific principles, are generally part of a recipe to build a product. The use-case in which the product is used can help build peace, but I do not see how “technology” per se could do it.

The technologies that come closer to the concept of peacekeeping are the ones used for deterrence. For instance, if you master nuclear technology in its various forms, your opponent may think twice before starting a conflict. In a deterrence scenario, where all parties have nuclear weapons, nobody would use them to avoid a “lose-lose” situation. This is how technology could save peace.

Del Vecchio: Some people now are using emerging technologies to include the civil community to participate in decision-making, for example, crowd platforms. Since the advent of the Internet, people are using it for participating or influencing public opinion and behavior. It is all about the intentions behind these technologies that will determine their dual-use. That can substantially change the nature of that technology.

Ladetto: I do not think the nature of technology can change. You can change the way you use some products or the applications you develop thanks to a specific technology, but I am not sure the nature of the technology itself changes. Let us take, for example, the story of ultrasound technology as related by Prof. Philippe Silberzahn in his book Bienvenue en incertitude ! (Welcome to Uncertainty). Ultrasound technology was used first to detect submarines during the First World War. After some progress and developments, it was used for medical purposes, allowing to detect if a fetus suffered from diseases of malformations. At the same time, the exact same device enabled the identification of the gender of children before birth, which, in some periods and some countries, resulted in forced abortion. I will not spoil the complete story as I strongly recommend the book, but considering this part already, do you really think it was possible to imagine all the numerous uses of that technology and the different implications in politics and society?

Air bombs

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Air bombs

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Del Vecchio: The same tools are being used for different purposes. Nearly every technology can be misused if the one holding power over that object desires to do so. However, some technologies are specifically related to their dual-use capabilities, such as nuclear weapons, commonly linked to Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). The dual-use paradigm has extensive ethical implications. It may concern a wide range of activities not necessarily related to technologies targeted under the dual-use umbrella.

Ladetto: Again, in my opinion, and I am not playing with words: if you misuse a technology, then the product simply does not work. The fact that a product is used to do “good” or “bad” is entirely independent of the technology itself. I am not entering into the discussion about doing good things in the short term that may result in a disastrous situation in the long term!

In terms of ethics, it is a little bit similar. Which ethics are we considering? I believe ethics depends on time, education, values, geography, and other factors. There are a lot of discussions about ethics these days, but less about the consequences of one given ethics with respect to another conception of ethics. I am not in the military, but what seems clear is that if you arrive in a physical confrontation, as mentioned by American generals, you do not want a fair fight, simply because you do not want to leave anything to chance. This has for sure implications.

Del Vecchio: How can you predict or assess possible events that might happen due to the implementation of potential dual-use technologies? How is the foresight process?

Ladetto: Foresight is not forecasting, so we do not do prediction. What we are working on are the potential consequences a new technology can enable. It might appear that I am playing with words, but it is not the case. I am interested firsthand in what new technology can offer, but in parallel, we are trying to understand what could be disruptive to the defense ecosystem. These could be new concepts, new properties, new values for given parameters, etc. We try, then, to find which new technologies or which combinations of technologies could enable it. There might be different ways to achieve it and this is where the challenge lies. Not waiting for something to happen, but acting to make it possible with what you have today.

We are in a world in which many things are unforeseeable, and you cannot predict when they will happen. What you can predict is the consequences of when these things happen. According to what you are looking for or what kind of impact it may produce, then you can decide. But, you have to prioritize because you cannot take care of everything. As a nation or as a company, you have to define what are the risks and what are their impacts for you; then you act to mitigate the most significant risks.

Honestly, you rarely can mitigate them all. That is what happened to an extent with the current pandemic. If you were or are working in the health sector, it was something that everybody expected to happen at some point; it was simply not on the priority list. Why? Because there were more important things to focus on. Simple.

Toy front

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Toy front

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Del Vecchio: But a researcher, a scientist, university institutions, or academia can evaluate possible risks related to their project —let us say, the development of emerging technology— and hopefully mitigate negative outcomes from the very start. However, I am aware that the potential dual-use implication may only become apparent at the end of the project, sometimes when it is already being marketed. While we are already deploying these emerging technologies, what kind of questions should we ask ourselves to assess them properly?

Ladetto: As you mention, you can assess the risks connected to a project, but not to technology. At least this is my opinion. Going back to the ultrasound example, how could you anticipate what would be done with a technology fifty, hundred years from its discovery, maybe in a completely different field, in a different society. It is simply impossible, and it should be completely fine!

There might be questions you could ask for the short term, according to given ethics, but what about the long term? What about the bigger picture?

I believe in the vision of Jules Verne who simply stated: “Whatever a person can imagine, one day someone will realize it.” And, once again, it seems more appropriate to anticipate the potential consequences rather than to debate if the cause —or one of the causes— should be prohibited.

Del Vecchio: So the “dual-use problem” has broader ethical implications on a wide range of activities not necessarily intertwined with technologies. What kind of implications do you believe this topic has on peacekeeping? For example, as technological developments advance at a lightning pace, how do you imagine peace-building actors in the future?

Ladetto: I do not know. But I can mention a vital aspect the peace-building sector will face in the near future. Everything that is now being developed, from the swarms of drones and autonomous systems, comes from the civilian world. Civilian industry creates technological applications that are later applied to the military or the defense sector. The technology per se is not developed as a secret, it is not developed by the armed forces in a secret laboratory; they are designed in universities, in the open with Ph.D. This makes it much more difficult to stop. Because if you stop it, you stop the economic growth. No serious politician will do that. How can you stop an area or restrict an area that provides jobs, income, taxes?

In the world we are in today, you have cutting-edge systems, completely open-source with a tutorial on how to build it. That has nothing to do with the armed forces. Maybe this is the main challenge that the peace-building sector will have to deal with in the future.

The discussion of peacekeeping is a political and economic issue and the cause is not technology.

(END OF THE INTERVIEW)

Final Remarks

One thing we know for sure: technological developments are speeding up with no chance of slowing down. Due to the increased number of skilled staff globally, the collaboration between industry and academia, investments in the research and development (R&D) phase, and overall globalization, the distribution and adoption of technologies are more widespread than ever.

When new technologies are being released to the market daily, and many of them are later used for purposes unintended by the inventor, the evaluation of the consequences related to dual-use technologies is urgent. The implications of dual-use technologies are adjacent to many variables, such as ethics, politics, economics, and a long list of other elements that are not necessarily related to the nature of technology itself. One same object can lead to various scenarios that we can hardly predict. This means that the extent of complexity that emerges from dual-use poses considerable challenges to the regulatory and ethical landscapes.

Toy conflict

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

Toy conflict

Mert Kahveci @ unsplash.com

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the "[...] responsibility for the identification, assessment, and management of dual-use implications rests to differing degrees across many stakeholders throughout the research life cycle: e.g., researchers, institutions, grant, and contract funders, companies, educators, scientific publishers, and other communicators, and regulatory authorities.” On the same note, Malcolm Dando, a leading advocate for stronger efforts at chemical and biological weapons disarmament at the University of Bradford, stresses that scientists should pay particular attention to the impact of their scientific advances, to a degree that is sufficient to “match the scale of the security problems that will be thrown up by the continuing scope and pace of advances in the life and associated sciences.”

Throughout history, we have seen many examples of science contributing to the development and distribution of technologies that were later used as weapons. Similarly, the military has for decades been the springboard for innovative solutions, responsible for designing state-of-the-art technologies that enabled further progress in areas not directly associated with defense mechanisms, such as in the health, education, and economic sectors.

In other words, the analysis needed to evaluate the impact of dual-use technologies requires a lens that integrates regulatory and ethics, which are both paradigms that are not linear or straightforward, and many times operate separately from the development of emerging technologies. In an ideal scenario, the evaluation of the potential outcomes related to dual-use technologies should focus on the objectives and goals of the stakeholders involved in peacekeeping instead of deciding to —or not to— hamper the development and distribution of these technological tools.

For that, regulators and policymakers need to see beyond the perils of weaponization and monitor the interests of political, economic, and social landscapes where dual-use technologies are later applied in order to pursue a sustainable society.

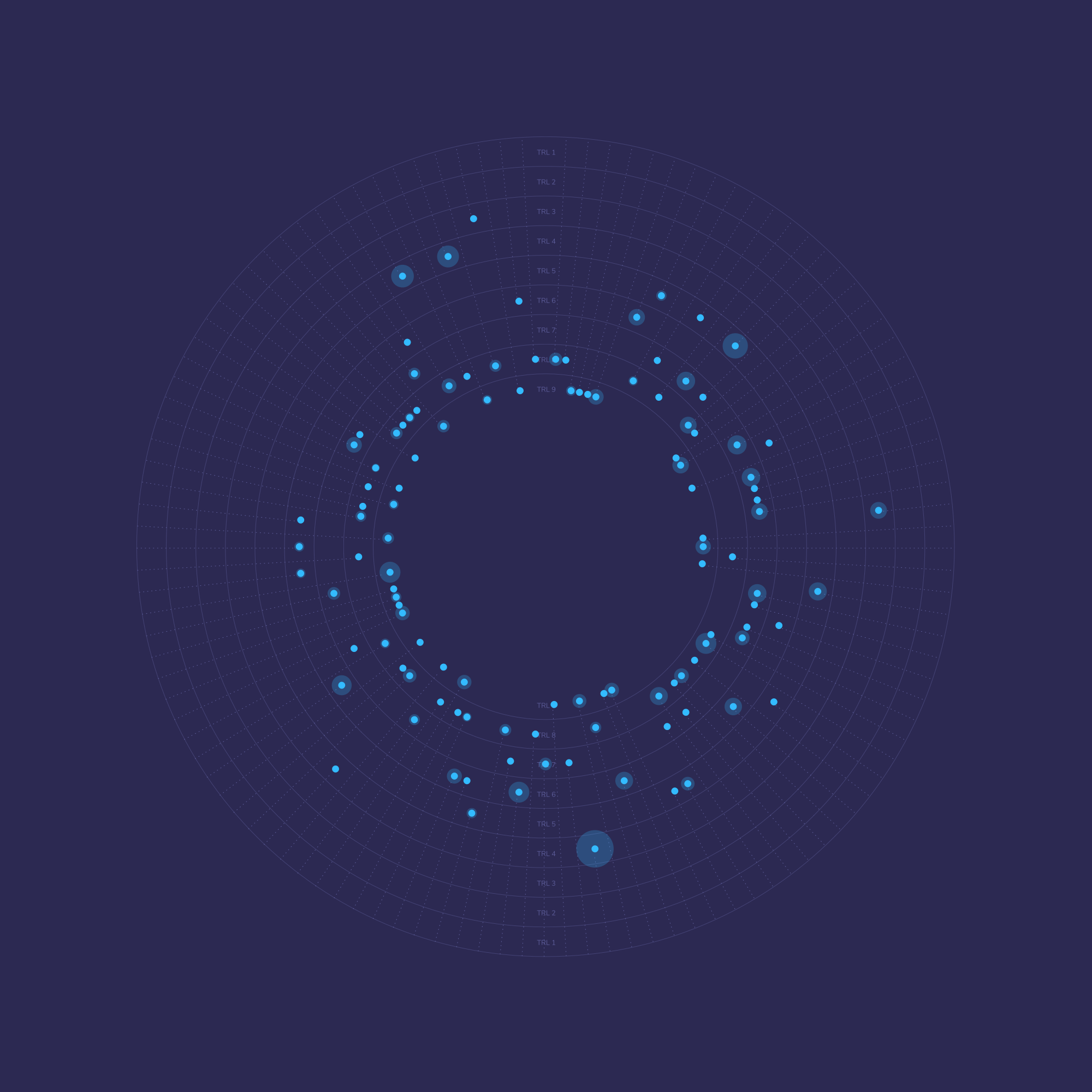

📌

As an effort to evaluate the sustainability level of emerging technologies, Envisioning, together with GIZ, developed the Sustainability Metric, a tool that intends to assess the potential impact of technology applications in three different dimensions of sustainability: economic, ecological, and social, as well as a fourth dimension displaying cross-cutting issues. Curious to know more? Please visit the Sustainability Impact Metric for additional insights.