Data-as-a-Tool to Empower Smallholder Farmers

Ariana Monteiro

Zubair Hussain @ Unsplash

💡

The year is 2030 and smallholder farmers are digitally literate. This means they can fully access the data they generate and interpret all sorts of farming-related information through simple data analytics available in text, video, and audio formats. Some choose to share entire data sets with extension service providers in exchange for training, facilitation, and coaching in farmers' managerial and technical skills. While others prefer to regularly sell disaggregated farm data (e.g., crop productivity, efficiency, and farming output levels) in digital marketplaces. Thanks to digital literacy, smallholder farmers have considerably improved their livelihoods, unlocking new sources of income by managing digital revenues from the data collected from their farming activities.

The future scenario presented above shows the many opportunities smallholder farmers could gain when sovereignly managing the data they produce. Yet, for this to happen, farmers will need to become digitally literate and an entirely new set of regulations will need to emerge.

Digital literacy is a transformational model that should happen progressively through partnerships among agricultural cooperatives, governments, stakeholders, producers, and consumers. This transformation will require educational resources to inform farmers about the data they can generate (and how to use digital technologies), as well as economic investments from both the public and private sectors to deliver the necessary financial support to these agri-food actors for them to be truly inserted in the digital transformation. This will help break a lifelong cycle that prevents smallholder farmers from thriving economically and socially —for years, they have been one of the most vulnerable social categories globally.

Besides empowering farmers through proper knowledge and economic resources to actively engage with the data they generate, the data gathered could help build global agri-food databases that provide knowledgeable assistance on many global challenges, such as the monitoring and predicting of weather changes, insights about crops' health, community support, and many more.

Ryan Searle @ Unsplash

Ryan Searle @ Unsplash

But this transformation is still far from being accomplished. The world of 2030 we hypothetically foresaw is radically different from the raw truth of today. While smallholder farmers lack considerable knowledge regarding digital tools (mainly due to limited access to technology) and the amount of data they generate (e.g., social media accounts, satellite images, geolocation, etc.), big tech companies keep profiting from this disadvantage. Opposed to this inequitable reality, we propose a future scenario in which we evaluate the expected roadmap governments, institutions, stakeholders, companies, and producers may face while achieving data sovereignty, control, and governance for smallholder farmers.

In the following sections, we disclose some transformation waves we consider crucial to reaching a data-empowered future, as well as some signals rooted in the present that corroborate our speculations of the future. You are now invited to explore this future scenario and work together to creating a more democratic digital environment for all.

Smallholder Farmers Recognize Their Data's Value

The collection, access, and use of farm data at the crop level should be granted with the explicit consent of the farmer. However, according to FAO-supported research on farmer's rights to data, information, and knowledge, information access is mainly held by large-scale farmers and service providers, and the data generated by smallholder farmers is generally gathered by stakeholders who control satellite imagery. Also, data management is not always consensual, and in most cases, it is not regulated by any digital framework such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Recent research uncovered cases where farmers claimed their data had been collected illegally by third parties, reporting that "[…] in 2017, a class action was brought by a group of chicken farmers in the Oklahoma District Court against a large food corporation and other chicken processors for allegedly sharing production data (e.g., type of feed and medicine used, and transportation costs) with third parties without the consent of 38 chicken farmers. The data was shared with third parties to keep farmer's payments below competitive levels. The key issues for the chicken farmers were that the processors’ data aggregation did not adequately anonymize the data, and it was unlawfully shared between the processors to reduce costs."

This lack of transparency on data ownership, data rights, data privacy, and data security leaves farmers out of digital transformations, especially smallholder farmers living in the least developed countries (LDC's). Accordingly, The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) states that in LDC's, only one out of seven people have access to the internet, with significant disparities between rural and urban areas. As a result, small producers are usually hesitant to willingly share their data because they feel unsafe or are unaware of the benefits they might receive when transferring data. According to a report released by the World Bank regarding the legal issues arising from the adoption and uptake of digital agricultural technologies, small producers do not know "[...] how data about their farm is shared, used, and reused by others."

Aboodi Vesakaran @ Unsplash

Aboodi Vesakaran @ Unsplash

The fact that smallholder farmers feel unconfident when sharing their data and have insufficient access to knowledge leads to an urgent need for capacity development. This effort could potentially help the most vulnerable agri-food actors have increased awareness regarding regulations protecting their data, and potentially empower them to take action whenever they feel their data is threatened by any possible misuse. However, it is not sufficient to merely educate smallholder farmers about legal frameworks and expand their access to digital tools.

It is not just a matter of accessibility, but usability as well. Many smallholder farmers have inadequate scientific data skills, and most of the digital content and tools available do not contemplate their needs or are not offered in their native languages. Data analyses and forecasts should be available for farmers through appropriate communication channels, and this information must make sense to them. Collaborations between government agencies, third-party actors, grassroots organizations, and the private sector must develop open data platforms that facilitate communication through all agri-food actors, and some emerging technologies employing simplified data sets and in a variety of languages, such as Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD), SMS, and Interactive Voice Response (a technological solution invented in the 1960s, and currently popular at call centers, which allows humans to interact with pre-recorded audio files through a telephone keypad or through speech recognition), could help bridge this process.

Yet, to enable data empowerment, smallholder farmers first need to understand and agree with the benefits of being digitally connected. Digitization cannot be enforced. When actionable information, location-specific and easy-to-understand data reach smallholder farmers, the agri-food sector could become less unequal. But, this would require an orchestrated coordination between stakeholders to translate, communicate and build the proper digitization infrastructure. This digital transformation is progressively advancing. In the following section, we disclose some current actions landowners, farmworkers, unions, farmers' associations, agricultural suppliers and services, protection agencies, governments, and NGOs are committing to for a data empowered future scenario.

Present Signals of Change

In 2015, Nigeria’s Edo State Government launched the first sub-national open data portal in Africa. The Edo State Open Data Portal currently releases several agricultural datasets, including registered fish farmers, fish farmer yield, cash crops, soil fertility, agribusiness enterprise, and veterinary clinics. Prioritization of datasets is done through an initial scoping process of all datasets held by the ministries, departments, and agencies and then by working with the commissioner to determine what can and cannot be open due to various privacy or security issues.

Based in Kingston, Jamaica, SlashRoots is a social impact organization working throughout the Caribbean. SlashRoots is currently working on a project to take data from the farmer's registry in Jamaica and turn it into a transactional platform. To do this, they are currently trying to understand the use-cases and how to store and display data securely. The overall goal is to make data more accessible and available to government agencies and third-party actors. The farmer's registry includes data points for 178,000 farmers, such as unique farmer ID, name, address, number of farms, information on farms regarding size and location, and production information.

Viamo is a mobile phone notification and survey platform for farmers in Ghana that uses SMS and Interactive Voice Response (IVR) technology to provide weather data and insights on early-season fertility for crops to unschooled farmers.

Red Zeppelin @ Unsplash

Red Zeppelin @ Unsplash

Farmers Earn Fair Rights to Manage and Secure Their Data

While in the first transformation wave, the goal is to increase access to data and enhance the development of knowledge capacity of smallholder farmers to interpret their data's value. The next wave should focus on the challenges that arise from data exchange: data collection, analysis, and storage, especially concerning data breaches, personal data sensitiveness, and ownership. As the agri-food sector progressively enters into the digital revolution, this sector is also equally more exposed to cyber threats.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in 2020, agriculture was the fifth most likely industry to record a data breach and yet the fifth least likely of any sector to invest in cybersecurity strategies. In fact, in 2021, JBS SA, the world's largest meat producer, had its data stolen in Australia and Brazil. During attacks on more prominent companies, cybercriminals also target smallholder farmers, selling their private information online to pressurize ransom payout. Redirection of invoice payments and ransomware attacks, for example, are actions that can allow criminals to block user access to files and data. As data breaches are increasing, smallholder farmers, who do not have the necessary economic resources to set up technological defenses in their day-to-day operations, will become more vulnerable to these attacks.

A critical step towards a safer data future is the establishment of laws and regulations that define and protect users' data rights. Governments could partner with data rights organizations such as #RestoreDataRights, The international Open Data Charter, and the Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition to understand how to govern data effectively in compliance with transparency, accountability, and equity. Once governments worldwide put in place laws that treat privacy and data as a civil and universal human right rather than a consumer protection matter, data sovereignty may flourish according to national or regional legal frameworks.

On the same note, data cooperatives and data steward consortiums could help farmers deal with data privacy consent, data rights, and portability, establishing codes of conduct between users and data brokers. The consortiums' role would be to codify legal forms and software rules to maintain the data owner's rights safe in the network. At the same time, these emerging data entities would carry data transfers from farmers to third parties on a confidential basis subject to legal inspections. These data entities would act as a steward, which could be a consortium of governments, the private sector, and civil society that defines how data is made sovereign and shared in a way that protects smallholder farmers and individual interests.

These proposals for regulating and protecting digital data will demand international cooperation from the public and private sectors, since the internet is rarely impacted by borders. The following section details some steps taken towards this transformation wave and works as an inspiration for other actors to take action and elaborate on new forms of regulation data exchange.

Max Kukurudziak @ Unsplash

Max Kukurudziak @ Unsplash

Present Signals of Change:

An agriculture data collection and software service called Farmobile developed an ownership framework that governs farm data ownership and control through a legal agreement asserting who can edit and access data. They also created the Farm Data Marketplace, where Farmobile collects offers from companies who want to use data and presents them to farmers, ensuring they receive payment. This payment then gets split between Farmobile and the farmer, 50/50.

eGranary is an initiative from farmers in Eastern Africa to “[...] empower themselves in both input and output markets.” Through the project, information is collated about farmers and their harvests and shared exclusively with other network members via mobile phones. This model is being replicated in different African regions. Currently, the Pan African Farmers Organisation (PAFO) is juxtaposing these regional projects to create a continental database once the regional ones are set up.

Farmers Lead the Digital Market and Profit From It

Farming data marketplaces are digital settings that allow farmers to share, sell or exchange data among different stakeholders. These marketplaces are crucial for smallholder farmers to achieve data empowerment. This last transformation wave discloses opportunities for international organizations, civil society associations, and the private sector to cooperate to support digital marketplaces.

We expect that by 2030, it would be possible for smallholder farmers and their associations (e.g., cooperatives) to decide how to use their data and control it in a data wallet, an online identity record. Ideally, these wallets would monitor worldwide developments in data regulations by deploying Automated Compliance algorithms, showing all data in different languages and making it easy for farmers to understand how their data is managed across the agri-food chain. Each farmer would see many cross-sections of how their data in the wallet exists in the digital realm, composed either by the information they are recording or data that third parties might collect about their farming inputs, personal records, etc.

When transmitted to outside parties, each bit of data would be encrypted and analyzed under parameters established by data cooperatives and consortiums to verify the protection of each farmer's transaction. At the same time, a decentralized data protocol within the data wallets would have to guarantee data privacy and security to avoid data leaks and breaches. The data wallets would be designed to sync with multifunctional digital marketplaces, allowing farmers to interact with suppliers, buyers, other farmers through peer-to-peer communities, and consumers that wish to buy food directly from the source. These platforms combined with certificates on the blockchain would provide traceability for farm-to-consumer processes, delivering accurate provenance and food processing information.

Finally, this digital ecosystem of 2030 would help farmers seek job opportunities, machinery, loans, seed offers, and finalize transactions using either crypto or fiat currencies, mobile money, or even exchange datasets as cash within the operations, providing farmers with the resources and opportunities they need to grow and thrive. As the population rises by 2030 while the demand for food and rural jobs escalates, the transformative power of digital marketplaces will become strategic to promote innovative business models based on smallholder farmer's data empowerment and achieve the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. The following section highlights some steps taken towards this transformation wave.

Joss Woodhead @ Unsplash

Joss Woodhead @ Unsplash

Present Signals of Change:

Portugal-based Agri Marketplace is a digital B2B solution connecting small and medium farmers with industrial buyers. This solution operates through the entire agricultural supply chain, and it is one of the most popular online agri-food marketplaces globally.

The Maano Virtual Farmers Market is an app-based e-commerce platform that connects smallholder farmers with buyers and traders. The project is funded by the UN’s World Food Program to help farmers in Africa sell their produce. Following its successful launch in Zambia, the platform is now being developed and tested in other countries.

In Mali, STAMP delivers a system that helps pastoralists secure reliable weather data and improve their ability to trade more profitably. The system guides herders to the nearest suitable supply of drinking water, provides alerts to grazing areas, connects them to markets, and allows the exchange of information that helps keep their cattle healthy.

The Roadmap Towards 2030: Challenges and Opportunities

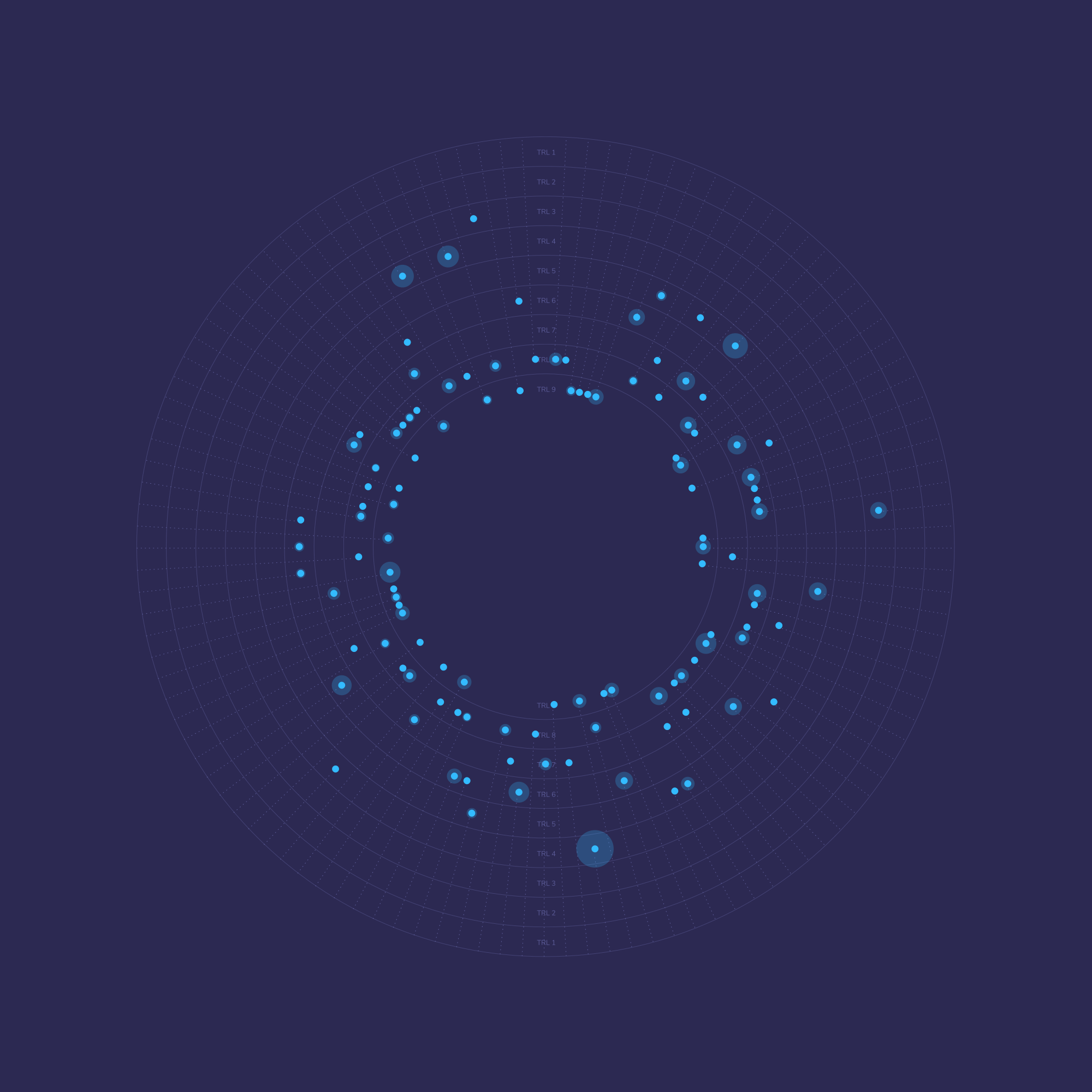

Data have enormous potential to transform the agri-food sector towards a more equal, transparent, and fair market. But, without a responsible approach to data exchange, this digital transformation may continue to serve only the most powerful agri-food actors. To assess the expected challenges and opportunities of a data sovereignty strategy, we have developed a series of evaluations that consider economic, social, political, and ecological factors in relation to the participation of smallholder farmers in the digital transformation, and how emerging technologies could play a role in supporting this goal.

Economic Opportunity: Reducing inequalities in food systems to improve the livelihood of smallholder farmers

There is vast potential to utilize AI data analytics to create more equitable food systems. Machine learning applications could examine patterns across large reams of historical data, providing insights and predictions to farmers on where to invest. This could subsequently lower risks for banks and lower interest rates, as well as increase smallholder farmers' chances of getting financial aid. The same technological applications could also help predict future production outcomes, helping farmers increase their yields, reduce overhead costs, and produce more fresh food for their communities while profiting sufficiently from responsible data usage.

Economic Challenge: Building the infrastructure to connect the last mile

The affordability of internet infrastructure can be a significant issue for many smallholder farmers, especially in the developing world. Besides the cost factor, the availability of sufficient bandwidth in rural areas is also a problem. To overcome the digital divide, the private for-profit sector has the opportunity to provide telecommunications and internet infrastructure. Yet for the internet to be widespread, governments may have to introduce transparent and regulated processes to ensure bandwidth is widespread and equal.

Social Opportunity: Bridging both generational and knowledge gaps through knowledge

Precision agriculture technology combined with agricultural extension programs at the local level may be the main ways of addressing rural poverty and food insecurity. The goal in the upcoming years shall be to transfer technology to smallholder farmers from all ages, support rural adult learning, and assist farmers in data problem-solving, while getting farmers actively involved in the agricultural knowledge and information system to enhance sustainable development.

Social Challenge: Enhancing smallholders trust and interest to embrace digitalization

To enhance digital literacy among smallholder farmers, it is vital to create distributed strategies capable of reaching rural communities in ways they can easily access. Digital strategies need to adapt every source of data to local languages and the most common technologies used by smallholder farmers, such as: radio, SMS, and physical training on the ground, while also providing communities with the technical or professional requirements for interpreting and making use of data. Engaging local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), foundations, community boards, and farmers' associations is critical to enhancing trust in the process.

Ecological Opportunity: Providing sources to innovate and adapt to climate change

With recent threats of climate change, more farmers require capital investment in agriculture and human capacity development to continue making their living from farming. Precision agriculture, along with data sovereignty principles in the hands of smallholder farmers, may provide them with more economic resources to manage climate risks, and thus, help plan and adapt to changes while exploring ways to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Ecological Challenge: Protecting human rights for biodiversity and safeguarding ecosystem services

Data come from connected servers, which need energy; technology needs chips and raw materials, which can be very polluting and rare. Innovations that ensure human survival must be multidimensional and understand the global climate emergency. It is useless for digitization to be disseminated if measures are not taken to mitigate the environmental impacts produced by the agri-food sector.

Political Opportunity: Unlocking data's ability to serve rural communities

Public sector actors may benefit enormously with the advance of data governance. Public entities and economic and statistical bureaus could benefit from smallholder farmers' data to guide policy-making and to better target rural communities in need of aid programs. Yet, public datasets should be anonymized to minimize risks while enhancing citizen's privacy. Personal information from farmers should be secure by design and used only when necessary to preserve the data’s analytic potential, scientific utility, or benefit to public programs, subject to prior informed consent and rigorous risk assessment.

Political Challenge: Establishing and periodically reviewing the compliance landscape

Technologies tend to change faster than policies do. Governments need to embrace compliance mechanisms that might help monitor and spot changes in regulatory frameworks, impacting the advance of data empowerment. It is essential to regularly review privacy protection policies to ensure they are still valid, and technologies such as Automated Compliance software, Automatic Legislative Tracking, and User-Defined Data Sharing, may be useful to overcome this particular challenge.

Ramadhani Rafid @ Unsplash

Ramadhani Rafid @ Unsplash

Closing Remarks:

The present future scenario speculates on very optimistic proposals, examining the political and societal challenges the agri-food actors will face in the digital transformation. It also assesses how emerging technologies may digitally empower smallholder farmers to sovereignly hold their data. These proposals and assessments may ignite discussions among small and big players in the agri-food sector and should work as a springboard to develop new solutions that consider smallholder farmers' data sovereignty as necessary as the crop. This article is part of a series of editorial pieces that aims to explore how emerging technologies can ethically help reconfigure data governance and data sovereignty for smallholder farmers through the redistribution of digital resources.