Strategies to Include Smallholder Farmers in The Digital Transformation

Ariana Monteiro

Lily @ Adobe Stock

Rikin Gandhi, co-founder and executive director of Digital Green, a collaborative digital initiative enabling solutions for rural communities worldwide, thinks "if we do not invest in data sovereignty, we will only generate more asymmetries of power." Foteini Zampati, a freelance consultant and former legal expert on data rights for the Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition (GODAN) until May 2021, believes that smallholder farmers need to have more access to knowledge and technology, as they "[...] are the primary source of value in the production." And for Puvan J Selvanathan, former head of food and agriculture at the UN Global Compact Office and the founder of the Bluenumber Foundation, "data is as important as the crop. There is no condition in the world that we will have food security where the understanding of the crop in whatever dimension is less crucial as the physical product."

💡

The interviews were carried out by Ariana Monteiro, a senior researcher at Envisioning, by invitation from the GIZ i4Ag fund to provide insights into the challenges faced by smallholder farmers to profit justly and equitably from the data they share. But before we jump into this conversation, we have complied a glossary to introduce you to essential terminologies used in this interview.

Glossary

Epistemic Injustices

Injustices related to knowledge. Includes exclusion and silencing; systematic distortion or misrepresentation of one's meanings or contributions. The interviewees use the term to describe the degree to which smallholder farmers are being left out of the discussions regarding data monetization in agriculture. Not only in terms of access to data, but also the knowledge access to understand data analysis to guide their future business decisions.

Data Sovereignty

This means data is subject to the laws and regulations of the geographic location where that data is collected and processed. Data sovereignty is a country-specific requirement that data must remain within the borders of the jurisdiction where it is originated. At its core, data sovereignty is about protecting sensitive, private data, and ensuring it remains under the data owner's safeguard.

Data Governance

A key challenge for digital agriculture worldwide lies in finding a balance between protecting the privacy and confidentiality of agricultural data and farmers’ economic interests, while leveraging data's potential for the sector’s growth and innovation. While data sovereignty is a principle that grants the user responsibility, a data governance framework makes it possible to share and monetize data without giving up control over the process.

Data Stewardship

The steward's role is to codify consent rules in both legal forms and software to maintain the owner's data rights in the digital network or software, no matter what. A steward could be an entity or a consortium of public-private civil society who define how data is made sovereign and can be shared to protect the interest of the individual participants in a network.

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

A regulation in European Union (EU) law of data protection and privacy guidelines for collecting and processing personal information from individuals across all its member countries. Aiming to create more consistent consumer and personal data protection across EU nations, the GDPR details how organizations can handle the information of those that interact with them.

no one cares @ Unsplash

no one cares @ Unsplash

By 2025, research suggests that around 463 exabytes of data will be created each day globally —one exabyte is equivalent to streaming the entire Netflix catalog more than 3000 times. This data can typically come from sensors, mobile phones, and satellites, similar to how companies currently process and gather information from users. The digital information produced by users generates valuable inputs for those analyzing this data, such as optimizing their businesses and facilitating many processes for the final consumer, sometimes even selling data to others. However, users are rarely compensated for the data they create, subsequently generating an unbalanced trade-off between data producers and companies, with the latter having a systematic advantage.

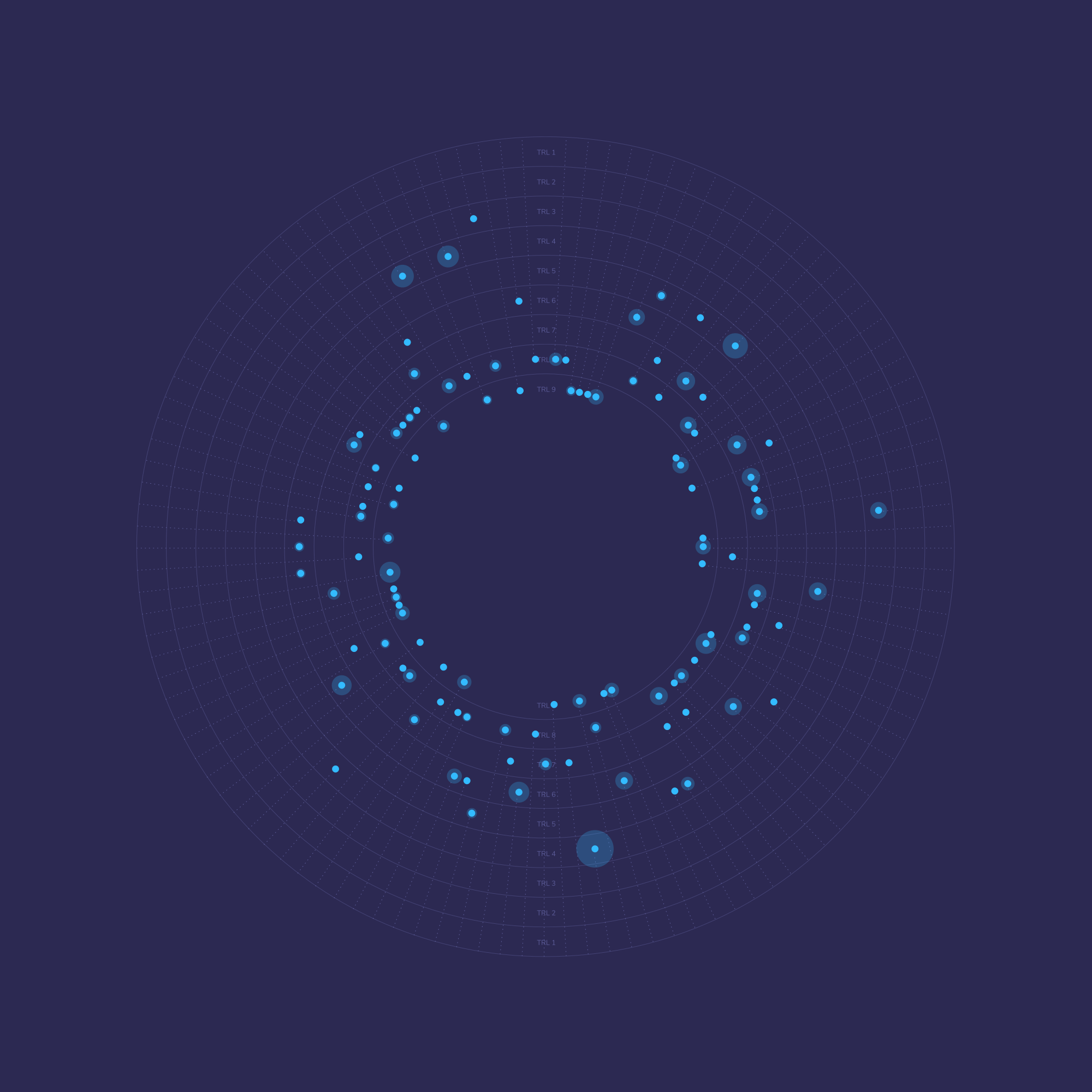

If we stress this logic to agri-food systems, this reality is even more striking. Farmer's data can come from multiple sources: satellites, GPS, social media, credit transactions, sensors scattered throughout their crops, and many other sources. Through these digital technologies, the data produced and shared by smallholder farmers are actually widening inequalities within the agri-food sector, instead of narrowing them by increasing access and leveraging ownership over the different types of data produced (personal and crop information, as well as financial data), according to recent research.

These inequalities are directly related to epistemic injustices, which are injustices related to knowledge access. This term describes how smallholder farmers are left out of discussions regarding data monetization in agriculture, not only in terms of access to data but also in understanding data analysis, which helps guide decision-making. But access to knowledge and data on its own does not solve the problem of data inequities. According to the interviewees, there are other fundamental aspects that sustain this power imbalance, too. Data sovereignty, for example, remains a challenge for smallholder farmers partly because the lack of laws and regulations in most countries protecting sensitive, private information at their geographic locations allows international companies to profit from their data without their authorization.

To shed light on many gray areas of the digital transformation in the agri-food sector, you are invited to explore an in-depth analysis provided by experts. The following interview provides insights that intend to bridge the digital gap between big tech companies and smallholder farmers, as well as leverage the role of emerging technologies in combination with regulations and legal frameworks.

Why is Data Sovereignty an Essential Topic for the Agricultural Sector?

For Foteini Zampati, overall digitalization could increase food production, improve farming quality and resilience, contribute to food and nutrition security, make the use of natural resources more efficient, and help farmers adapt to the effects of Climate Change. Yet, the benefits of this ongoing transformation are not equally distributed, especially when it comes to data. Rikin Gandhi believes, "[...] if we do not invest in data sovereignty, we will only generate more asymmetries of power. Big companies will only get bigger, and smallholder farmers will get smaller and even more marginalized." Furthermore, he states that in order to establish a data sovereignty framework, it must start from the very roots of economic systems.

Recent research performed by The Ceres2030 reports that from hunger to access to farming resources, the challenges faced by smallholder farmers are not reflected in the innovations provided by tech companies and stakeholders. Accordingly, "[...] every year, food rots in the field, or later on, because of inadequate storage. But nearly 90% of interventions aiming to reduce these losses looked at how well a particular tool, such as a pesticide or a storage container, worked in isolation. Only around 10% compared the many existing agricultural practices, evaluating what works and what does not." The study also found more than 95% of publications compiled in the Nature Research journals were not relevant to smallholder farmers' needs, as they did not involve them during research.

For Zampati, we need to look beyond data sovereignty, which is still considerably general and opaque, to data control which provides more tangible options to agri-food actors. In contrast, data control and data governance take the "smallholder farmers as the primary source of value in the production. For improving the entire agricultural sector, the focus should be on including them, not only stakeholders doing business." She adds, "[...] we need to provide them with the necessary tools, but we will only [do so] by engaging them in the entire process of data collection, sharing, and storing."

What is the Relationship Between Data Sovereignty, Control, and Governance?

Puvan J Selvanathan explains "[...] any degree of sovereignty does not describe the individual [level], it only creates a condition that is outside the individual. This means that the sovereignty of a sector leads to protectionism, borders, and other issues. That is the reason why data sovereignty should be a function of property rights. If smallholder farmers do not have the property right, they will never own it and, consequently, be unable to prove that someone else has breached their rights by trespassing their properties. That is the difference between control and everything else. Control is a subset, and you can only control what you own. If you do not own it, it is just a claim."

But control itself does not give users entire ownership over their data. User-generated content platforms, such as Facebook, pose an additional challenge as property rights are strictly related to agreements signed before using the platforms. Through terms and conditions, the only step owned by users is the creation of the data itself. "After that point, everything processed is fundamentally owned by big tech companies. And the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is so far silent on this matter," says Selvanathan.

Gandhi contextualizes this "[...] if the goal is to have control over data, it will require some data governance architecture led by the public sector to say that data sovereignty is extremely critical and must be protected at the individual level. Otherwise, data sovereignty will only mean that one can have access to data without being capable of sharing it for different purposes, for instance, monetizing it. In contrast, stewardship over data codifies rules in legal and digital forms; therefore, the data owner's rights remain safe in the network. For instance, if organizations are employing machine learning to process data produced by smallholder farmers, there must be a protocol to encrypt this data on many levels, allowing farmers to revoke access whenever they feel threatened by the use given to their data."

Red Zeppelin @ Unsplash

Red Zeppelin @ Unsplash

Are There Any Satisfactory Regulations?

Zampati reminds us of some digital strategies taking place in specific countries. For example, in January 2021, Germany released The Digital Strategy 2025, consisting of a package of measures that "aims to enhance and structure the responsible and innovative use of data provision and data usage within Germany and Europe, [...] ensuring that there will not be any data monopolies or widespread data misuse.“ She also adds that "some codes of conduct have emerged to fill the legislative void, setting common standards for data sharing contracts and providing fair and transparent governance structures for agricultural data."

These codes of conduct provide principles that the signatories agree to implement in their contracts. However, farm data flows are harvested from many actors, such as extensionists, advisory and finance service providers, governments, etc., before returning back to the farm in the form of aggregated and combined services. According to Zampati, "such flows potentially open up sensitive data that should only be shared with specific actors under specific conditions or should be anonymized to avoid harming the farmer’s interests and privacy. In the case of smallholder farmers, whose farm data often coincides with household data and personal data, are in the most delicate position to negotiate their data rights."

For Selvanathan, "the GDPR is a caveat to keep a degree of control over data because it merely gives users some rights and tells companies how to behave when handling data. This is problematic because instead of defining who owns the data and the obligations in terms of duty for someone else's property, it fixes a standard behavior for those processing and dealing with data." When it comes to smallholder farmers' data, there are some additional obstacles beyond establishing satisfactory regulations.

Why is it Difficult to Address Data Sovereignty for Smallholder Farmers?

In the current economic and political system, smallholder farmers are invisible in the eyes of the public. According to Selvanathan, once the worldwide population "[...] know [smallholder farmers'] realities, such as the lack of labor rights, education infrastructure, persistent hunger, etc., it could make it difficult not to have a duty of care." Selvanathan adds: "companies keep profiting because of that invisibility; the control lies in the gray areas of the agri-food sector."

The digitization of agri-food services, such as the collection, storage, and sharing of data coming either from producers' personal information, sensors coupled in their crops, or even satellite imaging, could well increase smallholder farmers’ household income and help them make more informed decisions. Yet, in practice, this is not happening for smallholder farmers. "If farmers are kept in the dark, it makes it easier for companies to keep profiting from farmers' resources and inputs. In many cases, companies gather data from them through sensors, mobile phones, or satellites without giving anything back. This lack of bargaining power between these two ends puts smallholder farmers at a systemic disadvantage. We need to provide farmers with the significance of getting the benefits of providing data," says Zampati.

Policies and regulations could safeguard farmers' data privacy, security, and ownership rights and avoid market monopolization, unauthorized transmission of data, and the inability to embrace smaller actors in the value chain. According to Gandhi, "if there is no appropriate policy infrastructure to grant data rights, from a technology point of view, there is nothing that can stop bad data practices. There is a lot of remote sensing data coming from satellites with maps of farms and fields. The question is, at what level of granularity does this data become personal data? If I can automatically recognize the plot boundaries of a farmer's field, does that become personal? For a smallholder farmer, their primary asset is their land, but at present, this matter is not covered by any regulation."

By achieving more transparent, fairer, and more responsible data governance frameworks over personal and non-personal data, privacy concerns could be alleviated in the future and potentially help farmers to benefit from data sharing. In 2018, the EU launched a new regulation about the control of non-personal data, which defines data on precision farming as non-personal data. According to Zampati, "[...] the new regulation emphasizes the importance of self-regulation within the data economy: it encourages the development of industry-specific codes of conduct, allowing for transparent, structured, and seamless sharing of data between service providers."

In order to include smallholder farmers in the digitization movement, decision-makers, stakeholders, governments, and non-profit organizations need to create a good safety net for farmers, which should include adequate regulation as well as the support to become digitally literate to manage the agency of their futures. This safety net will need to create an infrastructure that gives smallholder farmers the necessary means to understand the data they produce. Gandhi summarizes the challenge perfectly; "ideally, farmers should have data wallets where data is secured by interoperability and protection standards, enabling farmers the right to share their data in the way they want and monetize on marketplaces of their choice."

Beyond giving control to data producers, another way to ensure data sovereignty is to train people how to use the data they generate, and then raise awareness of the possible value behind that output. According to Zampati, "smallholder farmers are the primary source of value in the production. We need to provide them with the necessary tools: build policies and inform them about their rights."

The challenge is, how can data be put in the control of smallholder farmers and marginalized people, to give them a voice and the necessary tools to deal with power imbalance in the sector? "[...] The concept of data sovereignty shakes the foundations of current institutions: it requires from those who hold power to give up control", concludes Selvanathan.