On-Demand Economy

Lidia Zuin

Nick Filippov from BW PROject @ stock.adobe.com

Couriers: 2020 Superheroes

The much-anticipated game Death Stranding created by Hideo Kojima was released around the outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis, in November 2019. As if the game developer and writer could predict the future, Kojima imagined a post-apocalyptic version of the United States where couriers and logistics played a key role in safeguarding a few survivors isolated in their bunkers.

The world went into lockdown in 2020 and the streets were silent except for the sound of motorcycles and bikes delivering food, parcels, and medicine to those who were following WHO's directive for social isolation. As a society, we revaluated our priorities and the challenges faced by these workers who, as well as health and care workers, were deemed as "essential" and were placed on the front line of the unfolding sanitary crisis.

Small businesses benefited and even managed to survive the crisis with the help of platforms such as UberEats, Deliveroo, Glovo or iFood. Likewise, those who lost their regular jobs also found a way to keep their income through these companies, as argued by Manav Raj, Arun Sundararajan and Calum You (2020). But in spite of the fact that some people may cash in around US$7k a month for delivering food, do these numbers justify all the risks and undermined rights faced by these workers?

Workers Rights

In the past couple of years, the story of the self-made human revived by the gig economy was finally put under examination not only with strikes but also with a broader awareness of the class challenges faced by these workers. Documentaries such as GIG - A Uberização do Trabalho (2019) and even the drama Sorry We Missed You (2019) put audiences closer to the workers' perspective.

In an article for the University of Manchester, Cristina Inversi, Aude Cefaliello and Tony Dundon of the Work and Equalities Institute (WEI) point to the fact that platforms in the United Kingdom often use loopholes to undermine workers rights, as well as a lack of health and safety protections that are still not covered by policies in some countries.

However, in the United States, the California Department of Public Health has considered gig workers as "transportation and logistics workers," so they fall within a subsequent stage of vaccination after health workers. Companies like San Francisco-based Instacart, whose community unites over 500,000 gig workers, are even willing to pay $25 for workers to receive the vaccine. In Ireland, Just Eat declared to RTÉ that they are providing financial support for self-employed independent couriers through programs like "14-day Courier Relief Payment" to "those who may become ill or need to self-isolate as a result of the virus and can be claimed weekly in addition to the Covid-19 illness benefit made available by the Government.

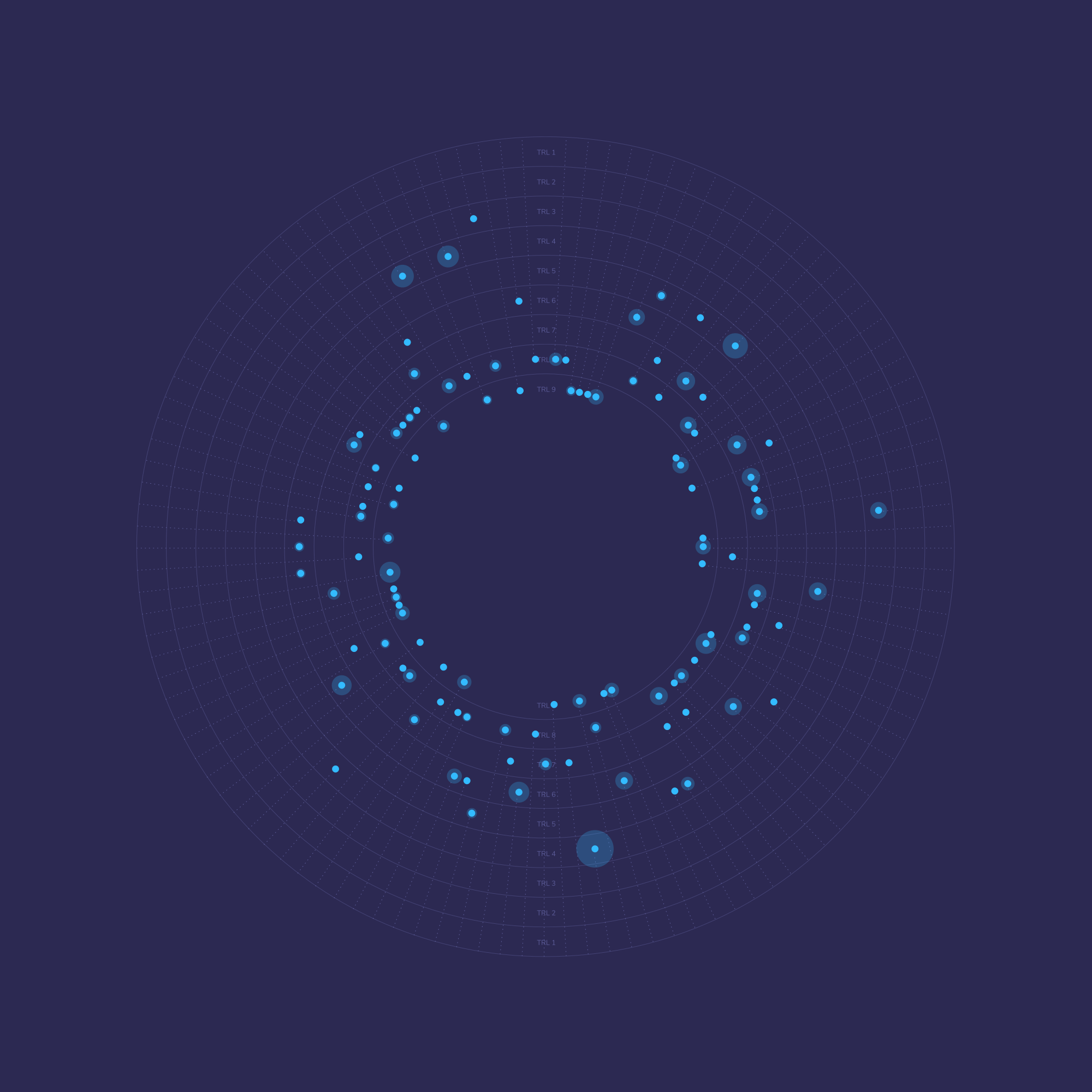

Data-driven Logistic Strategy

With the promotion of platforms that offer services of collaborative on-demand delivery**,** it is thus possible for both companies and customers to choose a courier based on a planned route that ultimately reduces shipment time and both human and economic resources. Through the analysis of data gathered by Mobile Crowdsensing Platforms, sensors, Machine Learning Weather Model, and GPS-based software, DHL in 2010 already launched its first Smart Truck with a route planning system that adjusts the route based on real-time data of the traffic, weather, and environmental conditions. With such information provided, drivers can avoid jams and operate more efficiently — according to DHL reports, the number of miles travelled was reduced by 15% as well as lower fuel consumption and CO2 released, a goal that could be ultimately achieved also with the help of emerging technologies such as Machine Learning Data Analytics.

In 2013, DHL also piloted in Stockholm the implementation of MyWays, a delivery system based on a Sharing Economy model that matches couriers with delivery demands after big data analysis of event processing and geo-correlation. Although the pilot was not expanded to other cities, it still reinforced sharing economy specialist Rachel Botsman's claim that "Sharing’s Not Just for Start-Ups," although incumbents more often choose to acquire and invest in the model or establish partnerships.

Another means to reduce time and increase efficiency when providing goods to consumers is taking advantage of the resources offered by the internet of things, such as smart fridges that automatically order groceries whenever product inventory is low. This was already tested by LG in 2017 when connecting Alexa to a model of a smart fridge, but the same strategy could be applicable to other devices like cupboards, laundry, and bathroom cabinets. In the case of Genican, this gadget monitors the trash bin and correspondingly sends information to create a shopping list, so not only the customer but also suppliers and retailers can access this information for more active logistic strategies.

Data-driven Adaptable Production

Logistics can otherwise be improved by taking a step back to production level. AI-based software can be used for predictive and anticipatory measures, applied to production models such as Industrial 3D Printing. This is the very core of an adaptable production approach for industries that, for now, are taking advantage of additive manufacturing techniques to sell hyper-customized products extensively. Examples range from Dr. Scholl’s custom 3D-printed shoe inserts to hearing-aid manufacturer Sonova, which has used 3D Printing since 2001 to produce patient-specific in-the-ear aids.

The novelty might be found in the way that adaptable production standards meet Anticipatory Shipping and Intention Economy. Both approaches are grounded in the ability to combine AI with consumer science, but while the first strategy is based on shipping products that are usually purchased by certain customers in certain areas, thus reducing delivery time, the last completely subverts the way markets are currently organized. According to Doc Searls, who proposed the concept, "the Intention Economy grows around buyers, not sellers" and the "buyer notifies the market of the intent to buy, and sellers compete for the buyer's purchase." Rather than having brands advertising products and services, Searls imagines a scenario like the following:

"In The Intention Economy, a car rental customer should be able to say to the car rental market, "I'll be skiing in Park City from March 20-25. I want to rent a 4-wheel drive SUV. I belong to Avis Wizard, Budget FastBreak and Hertz 1 Club. I don't want to pay up front for gas or get any insurance. What can any of you companies do for me?" and have the sellers compete for the buyer's business." (Searls, 2006)

"In The Intention Economy, a car rental customer should be able to say to the car rental market, "I'll be skiing in Park City from March 20-25. I want to rent a 4-wheel drive SUV. I belong to Avis Wizard, Budget FastBreak and Hertz 1 Club. I don't want to pay up front for gas or get any insurance. What can any of you companies do for me?" and have the sellers compete for the buyer's business." (Searls, 2006)

In order to attend to all these customers and stay competitive, new logistic approaches that involve robotics and AI could pose a new opportunity to acquire loyalty and preference among consumers.

Cloudy With a Chance of Delivery Drones

Companies such as UPS and Amazon have been working on the implementation of Delivery Drones since at least 2016, but even with the Covid-19 crisis, and an increased demand for last-mile deliveries, it was not enough for institutions such as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the U.S. to regulate and approve all the details to make the modality legal and active. However, pilot tests are already being performed in the U.S., especially when it comes to the use of drones for shorter distances.

In Fayetteville, North California, people can have their Starbucks, Dairy Queen Blizzards and other pastries and light meals purchases delivered by drones provided by Israeli company Flytrex. Orders won't be delivered to their backyard (yet), but customers can go to pick-up locations that are within a five-minute drone flight. Likewise, in 2018 Robomart experimented with a self-driving bodega that took fruits and vegetables to certain neighborhoods in California, which poses a possibility to combine strategies between autonomous delivery vehicles and Hyperlinked Supply Chain systems to cross information between inventory and customers' needs.

By emulating the mechanics of the classic farmers market but revamped with AI and drones, the insertion of robotics in logistics complements the possibility of adopting Hyperloops and Magnetic Underground Delivery Trail which forward parcels with no interference of the traffic or environment, but doing this via pipelines connected to distribution and consolidation centers. In fact, it is already speculated how Hyperloop One could partner with Amazon to deliver same-day purchases, thus allowing that the retail company reduce their warehouses from 119 to 18 in the U.S. and still increase deliveries from 66% to 80% as suggested on an upcoming whitepaper.